Move over, CSI and NCIS, there's a new game in town. Authors Eric and Natalie Yoder share some of their 'One Minute Mysteries' that can be solved with logic and knowledge of science — and without the aid of a magically fast DNA lab or improbable photo enhancement software.

Copyright © 2012 National Public Radio. For personal, noncommercial use only. See Terms of Use. For other uses, prior permission required.

IRA FLATOW, HOST:

This is SCIENCE FRIDAY. I'm Ira Flatow. Did you get a box set of "CSI" videos for the holidays, you know, the show with the magical blue light that analyzes all the clues? Any enhanced photo software photo thingie that makes impossibly blurry pictures clear again? That's my favorite, how they can magnify something, and it just suddenly fills in all those little pixels.

If this only-on-television sort of sleuthing is not for you, where they solve a horrible crime in an hour, how about a more cerebral kind of game, where you can solve a crime in a minute? Presented for your consideration, short mysteries for kids you can solve with a little logic and some science knowledge.

Want to give it a try? Our number 1-800-989-8255. Give us a call, and you can talk about it with my guest. Eric Yoder is a report with the Washington Post, his day job, but he's also co-author with his daughter Natalie Yoder of the book "One Minute Mysteries: 65 More Short Mysteries You Solve With Science!" Just published, they're both with us today. Welcome back. Happy holidays.

ERIC YODER: Thank you.

NATALIE YODER: Thank you, hello.

YODER: And thank you for having us.

FLATOW: You're going gangbusters with this series. I guess it must be well-accepted, Emily(ph) - I mean Natalie. I'm sorry.

(LAUGHTER)

YODER: It's OK. Yeah, they're doing very well. This is our third book. The first two were written when I was a middle school and high school, and now I'm a college student. So we've seen these books grow, and apparently everyone likes them.

FLATOW: Now do you start with a concept you want to get across and then write sort of backwards to come up with a story?

YODER: For some of them we find a common science fact or misconception, and then we build a story around them. But some of them are just problems that we see in daily life, and we decide to make them a story.

FLATOW: 1-800-989-8255 if our number, if you'd like to play along with us, and I'll read one or two if I can get the time for it of 65 more short mysteries, and maybe you can answer the question or solve the mystery of how somebody knew that. And I like the way the book has always been set up. You have the mystery on one page, and then you turn over the leaf, and you see the answer to the mystery on the next page.

YODER: Yes, we tried to do that so there's kind of an immediate reward, especially for children, rather than for example putting all the answers in the back of the book and making them fish around for them. We find that kids like to read several in sequence, and just having them page after page like that I think really encourages them to keep reading.

FLATOW: Natalie, as you say, when we first met you back in 2009, you were in high school. And now you're off at college. Are you going to be studying literature and writing or move on to something...?

YODER: I'm actually a sophomore at Penn State. I'm studying communications and political science. But I am taking writing-intensive classes, and in the future I would like to do writing for PR or marketing. So this has definitely helped.

FLATOW: Political science you think will be helpful?

YODER: Yes.

(LAUGHTER)

FLATOW: OK. That was one of the favorite subjects when I was in college many years ago, but that's good. And are the books actually being well received? You say you're selling a lot of them. But do you know if they're being received in high schools or middle schools? Are kids being introduced to them through classes in schools at all?

YODER: Yes, we've heard from many, many teachers both directly and through comments sent to the publisher that teachers like to use them to reinforce what they're teaching in the classroom. Sometimes they use them as homework assignments, sometimes as warm-up assignments during the class period or as maybe extra-credit assignments.

And we have just heard so many teachers tell us that they really, really find them valuable as a real-life way to reinforce what they're trying to get across in the classroom.

FLATOW: All right, I have a couple of contestants. I think it's Dante(ph) and Erica(ph) in Nashville. Hi, welcome to SCIENCE FRIDAY.

DANTE: Hello.

ERICA: Hi.

FLATOW: Hey there. OK, are you ready to listen to the story, the mystery, and maybe solve it for us?

DANTE: We're ready.

FLATOW: OK, here it goes: Ivan's father had bought a new smoke detector six months earlier, putting each one of them on each level of their house, one in the laundry room downstairs, one in the sunroom on the main level, one in the upstairs hall between the bedrooms.

The smoke detectors sent wireless signals to an alarm system. Ivan's father had asked him to replace the batteries and looked surprise when Ivan brought the smoke detectors to him, where he was working at his tool bench in the garage; that was where they kept the fresh batteries.

You didn't have to take them off their bases, his father said. You could have just taken the new batteries, opened each smoke detector where it was and switched the batteries there. Sorry, I guess I didn't understand what you meant, Ivan said. Can't we just change them here? Well, to do that sure, but we have to put each smoke detector back in the same place, or the alarm system won't work right, his father said.

They're - and they're all the same except that the color of one is more faded than the others, and one has dark spots. At least that tells us what we need to know, doesn't it, Ivan asked? And so I guess the question is: How do they know where to put them back? Dante and Erica, where do they know how to put them, or which one goes to where? Any answers to that?

(LAUGHTER)

DANTE: The one that was in the - it was in the sunroom...

FLATOW: One in the sunroom, one in the upstairs hall.

DANTE: That one's going to be duller, the color will be duller, or faded I guess.

FLATOW: Yeah, you got that. Let me go - let me read - that's very good. Let me go to the answer page. It says: the faded one must be the one from the sunroom, the brightest of the places, Ivan said, setting aside the one with the lighter color. And the dark spots on this one are mildew, meaning it must have come from a damp, dark place, the laundry room. That leaves the other one for the upstairs hall.

DANTE: Very good. Thank you.

FLATOW: Did you - do you study science in school, Dante, was...?

DANTE: I'm a third-year medical student, and my wife is a biology teacher.

FLATOW: Is that you, Erica?

ERICA: Yes.

FLATOW: Did your training help, you think, solve these problems?

ERICA: No.

(LAUGHTER)

ERICA: Common sense.

FLATOW: Just common sense. Well, thank you for playing along with us. I wish we had a prize to give you, but we don't.

ERICA: Thank you.

DANTE: Thank you.

FLATOW: Just the knowledge that you helped the rest of America solve the problem. Have a happy new year to you both.

DANTE: You guys, too, bye.

FLATOW: Bye. Is that typical of how it works?

YODER: Yes, some of them are set up kind of as the classic mystery story, where it must be one of these three things that happened or, you know, in whodunit terms, it must have been one of those three people who did it. And so you use your scientific understanding to, you know, eliminate possibilities and to, you know, match up causes and effects.

FLATOW: So you must be already thinking about the next book you'd like to take on. Do you think about making each one topical, different topics, or do you mix them all up in the book?

YODER: We mix them up depending on where we get the ideas. We have kept a folder of ideas just working on it over the last several years. And so the first book was of science stories. The second book, of course, was stories based on more mathematical principles, and of course this one is science again. So it is a little easier to get science-based stories and ideas because there's just so much of science around us in everyday life.

FLATOW: So you - Natalie, do you come up with ideas from things you see on TV or where?

YODER: Some of them are from things we see on TV, but a lot of the concepts, again, come from daily life. And some of them are just facts that I learned in school or we've encountered at home or on family vacations. And science is all around us. So is concepts in math. And sometimes you just have to look into things and find the mystery within them.

FLATOW: There you go. Let me see if I have time for one more to read. Let's go to John(ph) in Atlanta. Hi John.

JOHN: Hi, how are you doing?

FLATOW: All right, ready to play? Here I go.

JOHN: Yeah, I'll give it a shot.

FLATOW: Hey, I had an old picture up of my grandma looking just like that, only it wasn't a costume to her, Cassandra said, as Ingrid walked into the homeroom. She said they actually thought you look cool. Their school normally had a dress code, but it was Halloween, and everyone had come in that day wearing costumes. Ingrid was dressed like a hippie. She had a tie-dyed shirt, beads, sandals and sunglasses with orange lenses shaped like hearts.

Ingrid took off the sunglasses for class, but she put them back on when it was time to get ready for the Halloween party in the afternoon. The class was decorating the classroom and painting signs for the school parade. Kahn, who thought he was funny, was hanging decorations upside-down. Preston was pretending to sword-fight in his pirate costume with a paintbrush. And Ricky was playing with fake blood after putting some on his zombie costume.

When it was almost time for the parade, Cassandra noticed that one of the signs had been decorated with a red, rather than an orange pumpkin. OK, who's the joker here, Cassandra asked? John, do you have any guesses, and reason it out with us.

JOHN: Right, well, I would guess that the person who painted the pumpkin red was the person who was wearing orange sunglasses because that changed the way she saw the light. Was that Ingrid as the hippie?

FLATOW: Well, let's go to the answer page. Flip over - or there is a picture of someone wearing sunglasses. She looked around the room for a guilty face. I see now, Cassandra said, it's your orange-colored sunglasses, Ingrid. They make everything look the same color to you. They're acting as filters, so the light of only one or some colors come through to your eyes, but other colors are blocked. What you thought was orange paint is actually red. Take off those sunglasses, and you'll see.

Oops, Ingrid said laughing, I guess we'll just paint some flames on it and call it a pumpkin on fire.

(LAUGHTER)

FLATOW: Very cute ending. Thank you, John, you got it right.

JOHN: Great.

FLATOW: Thanks for playing along with us.

JOHN: Thank you very much.

FLATOW: You're welcome. Have a happy new year.

JOHN: You too, bye.

FLATOW: It seems like you don't have to be a kid, Natalie, to enjoy playing these little games with the puzzles here.

YODER: Well, I hope not. I hope that people at all ages can enjoy them.

FLATOW: Yeah, and do you laugh at the things you see on TV sometimes, like I started out by talking about CSI and weird kinds of instruments they have that nobody has?

YODER: I'm actually a big fan of "CSI," but it's also cool to be able to write them and to know that children will be able to solve them.

FLATOW: Yeah, so when can we see the next book?

YODER: Well, we're working on it right now. We're thinking about doing something math-oriented again. But we have some other ideas, and we might try a different format the next time around. So it will be some time, but in the meantime, we're really happy that this book just came out, and it's, you know, now available along with the other two.

FLATOW: All right, thank you very much for taking time to be with us, and have a happy holiday.

YODER: Thank you.

YODER: You, too, thank you.

FLATOW: Eric and Natalie Yoder, author of "One Minute Mysteries: 65 More Short Mysteries You Solve With Science!" We're going to take a break, and when we come back, we're going to talk about probably a renaissance scientist you've probably never heard of because so many of his ideas were wrong. No wonder you didn't hear about him, but still an interesting guy. Stay with us. We'll talk more about him when we get back after this break.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

FLATOW: I'm Ira Flatow, this is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR.

Copyright © 2012 National Public Radio. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio. This transcript is provided for personal, noncommercial use only, pursuant to our Terms of Use. Any other use requires NPR's prior permission. Visit our permissions page for further information.NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a contractor for NPR, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of NPR's programming is the audio.

View the original article here

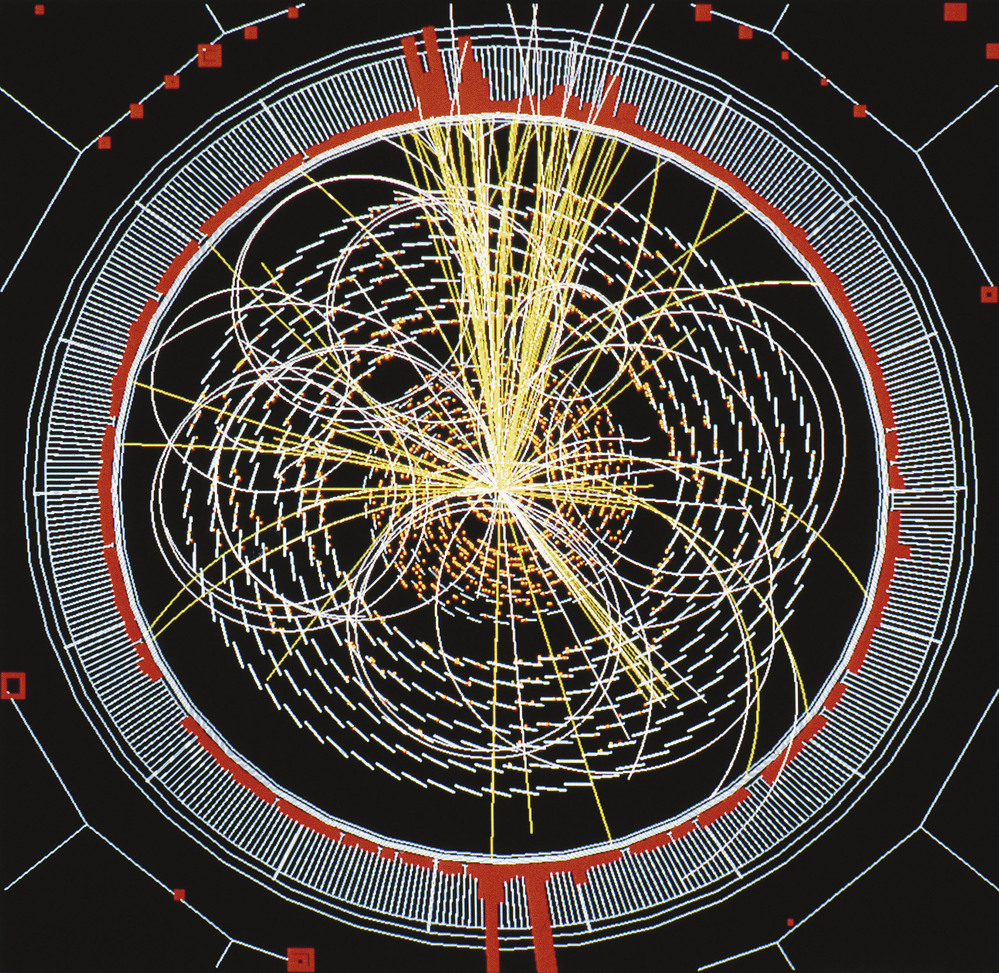

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider announced the discovery of the Higgs boson on July 4, the long-sought building block of the universe. This image shows a computer-simulation of data from the collider.Barcroft Media/Landov

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider announced the discovery of the Higgs boson on July 4, the long-sought building block of the universe. This image shows a computer-simulation of data from the collider.Barcroft Media/Landov

Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wis., use eggs to see if the Asian strain of the H5N1 bird flu virus has entered the U.S. in this photo from 2006.Andy Manis/AP

Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wis., use eggs to see if the Asian strain of the H5N1 bird flu virus has entered the U.S. in this photo from 2006.Andy Manis/AP