Writer Christopher Bonanos tells the story of analog instant photography and the man who invented it—Edwin Land, the scientist and co-founder of the Polaroid Corporation. Plus Flora Lichtman visits New York's 20x24 Studio to capture a super-sized Polaroid camera in action.

Copyright © 2012 National Public Radio. For personal, noncommercial use only. See Terms of Use. For other uses, prior permission required.

IRA FLATOW, HOST:

Right now, we're going to talk about the invention that changed how we picture the world. Do the elements of this story sound familiar? Listen, it's a start-up company that's created in a garage. A genius inventor, of course, is in charge of this thing. The latest technology combined with great design into a device that everyone had to have it. Sounds like Apple, doesn't it? Actually it's a true story of one of Steve Jobs' heroes, Edwin Land, the man behind Polaroid cameras. You know, those cameras that you just point, you shoot, spits out that photo. People used to wave it around a little bit. They didn't have to, it turns out. In the '60s and '70s, everybody had to have one. Hard to believe they're such a rarity now but they are. Here to tell us more is Christopher Bonanos. He is author of "Instant: The Story of Polaroid." He's also an editor at New York magazine. Thank you for coming in today to talk about this.

CHRISTOPHER BONANOS: Great to be here.

FLATOW: All right. Tell us about Edwin Land first. He really was the creative genius behind Polaroid, right?

BONANOS: He was. And he really built the company on the spot where art and science meet. And, you know, he conforms to that Silicon Valley mold. He was a college dropout who saw something to do with an invention he had and then ran with it for the rest of his life.

FLATOW: And he had some history. He effectively created the U-2 spy plane. He advised presidents.

BONANOS: That right. He was...

FLATOW: He made goggles, the special Polaroid goggles for the military, right?

BONANOS: That's right. He was a really public figure in his time in the way that Jobs was in ours.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And did he run Polaroid like Jobs ran Apple?

BONANOS: Well, somebody who knew both once said to me that Land was the kinder genius. You know, he wasn't a ranting screamer in that way that Jobs could be as we all know from the biography of him that's out now. But he certainly exerted pressure in the same way, you know. All his employees have stories of calls from Land at 3:30 in the morning when he'd say something like, I was thinking about an idea. Could you come in and talk it through with me over breakfast at 5? And they would go.

FLATOW: Wow. And there is also a very famous pictures about, you know, Steve - the iconic Steve Jobs' presentation where he's sitting at a desk in a big auditorium. Land did that first.

BONANOS: Land did it first.

FLATOW: It's almost like a black and white copy of what he was doing.

BONANOS: It's uncanny. Yeah, he really - he figured out at the shareholders meeting of Polaroid starting in the mid-'60s did not have to be just some financial officer getting up with a spreadsheet and sort of reeling off some numbers about the previous year and doing a little speech. Instead, Land, you know, he'd have stages built, and there would be music, and there would be fresh flowers and things. And, you know, it would be a show.

And he would eventually take the stage after some warm up, and he would have the camera or whatever product was being introduced in his hand and he would sort of talk about it philosophically and explain more than sell. And by the time he was done, if there was a new product coming out that year, you just - you were brought into his world, and you had to have this thing that you had never heard of until that moment.

FLATOW: Our phone number is 1-800-989-8255, talking with Christopher Bonanos, author of "Instant: The Story of Polaroid." The pictures in this book are just worth the price of the book itself. They're just gorgeous pictures. And one thing you note from reading the book is in his heyday, all these famous artists had to have a Polaroid to use. What was special about the Polaroid camera?

BONANOS: Well, it was a number of things. Some of it was the instant feedback aspect, you know. If you were taking pictures - and you've got to remember that, especially in the early days, you were sending them out to a lab often in another city. You got them back by now, it took you a week. And if you were photographing something in the moment - an event or shoot or whatever - it was gone. You couldn't get it back and do it again.

So to have your pictures suddenly in 15 seconds, which some of the black-and-white film develop in, was a miracle, you know. So some artists just used it for that immediacy. Others just were besotted with the color palette. You know, the dyes in Polaroid film don't look like the dyes in other color films. They're more saturated and they just - it's hard to describe the difference, but they are unique and they look like something all their own. And, you know, a lot of people really liked Polaroid color and went with it.

FLATOW: And there are also some artists, like Mapplethorpe, who - if he took a picture of a nude body, he'll - it wasn't coming back from the lab.

BONANOS: That's really true. The cops might have shown up if they've seen those, you know, especially in the early days. He was doing that very strongly, homoerotic stuff. And, you know, the privacy and the intimacy that Polaroid photography provided was useful to him as he developed as an artist.

FLATOW: And you have a couple Polaroid cameras with you.

BONANOS: I do.

FLATOW: How did they evolve? Show us what you have. Let's do a radio demonstration.

BONANOS: I was just going to say...

(LAUGHTER)

BONANOS: ...pictures on the radio, right, you know? The earliest ones are of a form that's looks very old fashion now. This is a big camera with bellows that unfolds...

FLATOW: Unfold it.

BONANOS: ...and you focus it by shifting the bellows forward and back.

FLATOW: Oh, that's right.

BONANOS: It has a rangefinder on top. And they are the earlier form of the film where you pull a paper tab outside of the camera after it's fired.

FLATOW: And people would wave it around, thinking they had to dry it off.

BONANOS: That's right. Well, in the early days, it was wet. You had to coat the black-and-white film with this sort of little swab of plastic goo.

FLATOW: An applicator, I remember that. Yeah.

BONANOS: That's right. And it smelled awful and it got on your fingers. It was a pain. And even after that went away, people kept shaking. And they do to this day. They get a picture out of an old camera or something that's bone-dry and they wave it in the air with this idea that it makes it develop faster or something. I think it's just a - the thing about a Polaroid picture is that it shouldn't work. It's way too complicated to put into a little packet and develop by itself. It shouldn't work. And people feel the need to help it somehow. You know, they will let the magic out.

FLATOW: Yeah. They had to do something with it because it's - it can't be magical on its own.

BONANOS: That's right. They got to help it. The other camera I have is from the later series that began with SX-70 in 1972. And it folds down and up...

FLATOW: Oh, yeah.

BONANOS: ...with a little strap on the side prop it up. And this is one of the later models that focuses, if you can believe it, with sonar. It has a little panel above the lens that sends out a ping like a bat, an ultrasonic ping, and it bounces it off the subject and the lens spins to focus. It's - I think it was the first commercially available camera that focused automatically.

FLATOW: Yeah. And then they got to be - they wanted to make a really hot consumer model in the Swinger.

BONANOS: Well, that was a little earlier, that's right. In 1965, there was a big push. Color film had just been introduced a couple years earlier, and they wanted to start selling more black and white again because the color was so popular that nobody is buying the black and white. So they made a very inexpensive camera that shot only black-and-white pictures. They got the price of the camera down to 19.95 and they marketed it to teenagers. And it worked. They sold, you know, I think it was seven million of those cameras.

FLATOW: So what was the draw on that camera?

BONANOS: Well, it was very cheap. It made OK pictures. There were very small, but they, you know, it was fun. And it looked groovy. It was white plastic. It looked like a big sort of bubble. It was, you know, kind of mod-looking. And they had one of the great jingles of all time in the TV ads. It was called - the ad was called "Meet the Swinger," and the tagline was, it's more than a camera, it's almost alive. It's only $19.95.

FLATOW: And Ali MacGraw was the model.

BONANOS: That's right. There was a model in the ad who nobody knew. She was just some photographer's assistant who was doing little modeling in New York. And five year's later, she was the biggest movie star in the world.

FLATOW: You just gave yourself away with the word groovy.

(LAUGHTER)

BONANOS: Yeah. Well...

(LAUGHTER)

BONANOS: I spent a lot of time in 1965 while working on this book.

FLATOW: Yeah. Well, we - I remember - we lived through it. I remember watching all these cameras. Remember, there was one you had to really rip the back out really hard to get - because they were squashing the chemicals together, right?

BONANOS: That's right.

FLATOW: It was developing right there in a little pouch that was part of it.

BONANOS: That's right. When you pull the tab out of the side of the camera in the older forms, you're putting a positive and a negative together, and there's a little sack called the pod of developer. It's about, what is it, a tenth of an ounce or something? It's very small amount of gooey stuff. And as you yank it out of the camera, you're breaking that pod open and you're pulling it between a pair of rollers that smears the fluid between the positive and the negative. And then the dyes start moving in the color film across from one to the other. So you actually had to give it a thug with a certain amount of vigor.

FLATOW: Yeah. The smear is the technical word (unintelligible).

BONANOS: That is. Well, you know, inside Polaroid, the technical word for the stuff was the goo.

(LAUGHTER)

BONANOS: You'd actually see it on the technical documents. There'd be a column marked goo.

(LAUGHTER)

FLATOW: Let me see if we'd get a caller here from Christian in Richmond, Virginia. Hi, Christian.

CHRISTIAN: Hello.

FLATOW: Hi there.

CHRISTIAN: How are you doing?

FLATOW: Hi there. Go ahead.

CHRISTIAN: Yeah. I just had an interesting personal story about it, because my father told me about my grandmother used to be, you know, secretary for him, Mr. Land, back in Boston in the '40s.

BONANOS: No kidding.

CHRISTIAN: And he had offered to give her, what was it, stock of his invention just before he was coming out with it. And I thought it was a nice touch to be - he's obviously a very kind person. I heard you mentioned that earlier in the show.

FLATOW: So she must have been a gazillionaire after that, right?

CHRISTIAN: Unfortunately, no. She had to turn it down because she was starting a family and she didn't - I guess she didn't have enough faith in it or whatever. She just needed to have money right then and there. But yeah, we missed out on the...

BONANOS: What was her name?

CHRISTIAN: Her name was Bernice.

FLATOW: Hmm.

BONANOS: I...

FLATOW: Last name? Or you don't want to give it out. You don't have to give it out.

BONANOS: No, no. I'm just curious because I've ran a couple a lot of old place, names and research. No. There are many stories of Land being a sort of generous soul. You know, Polaroid had the benefits available to everyone. He really believed in creating a work environment that was, you know, a lot of profit sharing and sort of open, you know, he got rid of the factory time clocks at one point because he thought it was a good thing to do.

FLATOW: How did he come up with the idea?

BONANOS: Well, the company was built on another product entirely, the polarizing filter. And that product was tremendously useful and applicable during the war in all sorts of military stuff. And as war surged and wind down in 1944 and '45, he needed something new. And on a vacation at the end of '43, he and his daughter were in Santa Fe - she was three - and they were taking pictures all day. And she looked up at him and said, daddy, why can't I see the picture now? And he said, well, hmm.

And the story goes that he sent her off to be with her mother for a few hours, and he walked around the resort they were staying in, working it out in his head. He once said he worked out the whole thing in three hours except for the details that took from 1943 to 1972 to solve.

FLATOW: Minor details.

BONANOS: Right.

(LAUGHTER)

FLATOW: All right. So the devil is in the details and in solving the Polaroid problem.

BONANOS: Yeah.

FLATOW: Was it a secret that no one else could do? Why was it just one Polaroid? Why were there not competitors?

BONANOS: There were - he was a master patenter. And in fact, the amazing coincidence is that on that day in 1943 when he was on vacation, his patent lawyer also happened to be in Santa Fe on vacation. And that night, he went over to the guy's hotel room and started dictating. Even after that, though, they were very careful about secrecy, and they locked everything up with patents. And it meant that they had, you know, 100 percent market share for instant photography, and the profit margins for many years were fantastic.

FLATOW: Fantastic is the book "Instant": The Story of Polaroid," though, with Christopher Bonanos. We're going to also bring in now - Flora Lichtman is here with our video pick, which involves working with...

FLORA LICHTMAN, BYLINE: None other than Christopher. We did our video pick this week about a Polaroid camera.

FLATOW: Not just any Polaroid camera.

LICHTMAN: No, no. That would...

FLATOW: Too tame for us.

LICHTMAN: Abslutely. This is almost one of a kind. It's five of a kind. And it's the biggest Polaroid living - biggest living Polaroid camera.

FLATOW: This is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR. And where is it? Where did you find this camera?

LICHTMAN: It's in New York at the 20x24 Studio, and that's a hint, actually, about the camera itself. So the camera is called the 20x24. It was built in the late '70s - Christopher has more details on that for sure - and it now lives at the studio in New York. And it's called that because that is the dimensions of the snapshot. It's a two-foot-tall snapshot.

FLATOW: Snapshot.

LICHTMAN: So - and the camera itself...

FLATOW: Instantly.

LICHTMAN: The camera itself - OK. So you're imagining a Polaroid camera - or I am, in my head. Now, imagine that it's 235 pounds. And when it spits out its instant photographs which is - it works in a similar way to how Christopher just described where it goes through rollers, but it's like - the whole - the scale of everything is almost hard to imagine.

FLATOW: And you don't have to imagine it, luckily in this case, because we have up as our video pick of the week. It's up there on our website. You can download it also on iTunes. It'll be ready when we get it up there and - yeah, on YouTube, it's up there. You can see the camera. You can see Flora is having her picture taken, a giant photo.

LICHTMAN: The star is really the camera, folks.

(LAUGHTER)

LICHTMAN: Believe me.

FLATOW: And this is something that photographers use and a lot of artists.

LICHTMAN: Many photographers. Andy Warhol, Chuck Close uses it, Annie Leibovitz. William Wegman has used it. And the thing about these pictures that, you know, it sounds amazing. You have a headshot of yourself that's 20 inches by 24 inches, but the reality of that is that you see things on your face that you never wanted to see. I mean, every pore in your skin is like a cavernous hit that you - I'm just speaking for myself.

(LAUGHTER)

LICHTMAN: Lady Gaga, I know this. She also has been photographed by this camera. She opted for something less close. She's a smart lady.

FLATOW: Well, let me ask both of you. What is the state of film? I mean how much film - they don't make the film anymore, right, Christopher?

BONANOS: Polaroid has got out of the film business. They dropped out in 2008. But there are a few options left to people who shoot Polaroid pictures. The older peel-apart stuff, one format is still made by Fujifilm in black-and-white and color, and I shoot a lot of that. And then the more familiar one with the white border that's out the front, SX-70 and the ones that came after it, are - the factory was bought by two enthusiasts in Holland. It was the European factory. And they reincorporated as something called the Impossible Project.

And they've spent the last almost three years trying to reformulate this film with no access to Polaroid's ingredient supply chains. They had to come up with chemical work rounds for everything. And the first batches of film were sort of beta tests or maybe alpha tests. They weren't all that great. The new stuff is shockingly similar-looking to Polaroid film. They've really, really sort of brought it around. The new color film looks like it's supposed to look.

FLATOW: Is it that because Polaroid had a lock up in patents?

BONANOS: Well, the patents mattered less as the years went by, but what they did was they would buy, you know, a hundred truckloads of some chemical that goes into the film. And nobody else made it because nobody else wanted it. And these guys - it's a dozen people in a factory in Holland, they can't order any volume.

FLATOW: And yet they used a limited amount of film on you, Flora.

LICHTMAN: Yeah. We were very lucky to have it used. I think they have 1,000 black-and-whites left, so they're much more careful about those. We had color taken and there's 15,000 pictures left for that. And anyone can book time with them. If you're interested in a super-sized holiday card maybe, you could just - I don't know if you could mail that but...

FLATOW: We should bring it in to the studio and take a group photo here, yeah.

LICHTMAN: Absolutely.

FLATOW: That's our video pick of the week up there on our website at sciencefriday.com if you want to see this camera if you want to see a giant 1-1/2-by-two-foot picture, just unbelievable. Thank you very much, Christopher, for coming in. Christopher Bonanos is author of "Instant: The Story of Polaroid." Those of us who lived those years are very happy that you wrote that book.

BONANOS: Excellent.

Copyright © 2012 National Public Radio. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio. This transcript is provided for personal, noncommercial use only, pursuant to our Terms of Use. Any other use requires NPR's prior permission. Visit our permissions page for further information.NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by a contractor for NPR, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of NPR's programming is the audio.

View the original article here

Most hydraulic fracturing in California is done to extract to oil in areas like this field in Kern County. The state is drafting fracking regulations for the first time.Craig Miller/KQED

Most hydraulic fracturing in California is done to extract to oil in areas like this field in Kern County. The state is drafting fracking regulations for the first time.Craig Miller/KQED

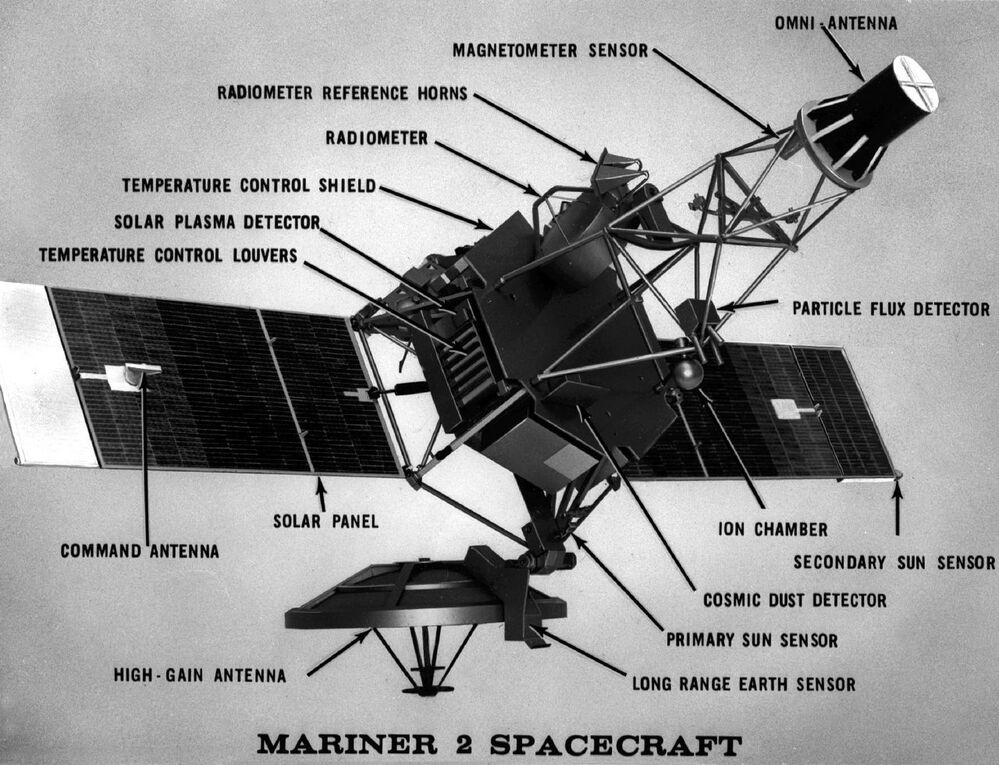

Scientists show off reams of data collected by Mariner 2 as it passed by Venus. The probe flew by the planet on Dec. 14, 1962, and scanned the surface for 42 minutes.NASA/JPL

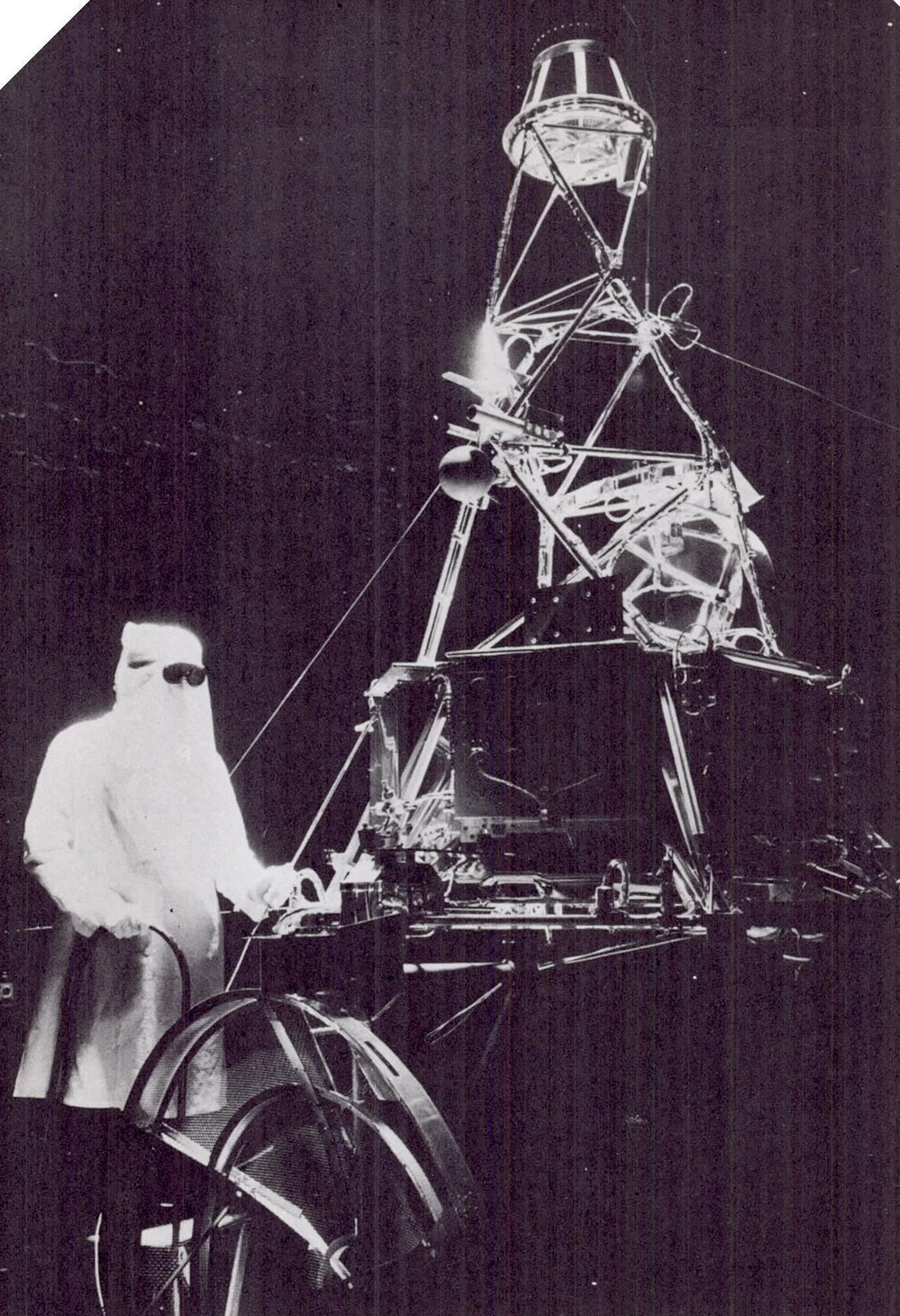

Scientists show off reams of data collected by Mariner 2 as it passed by Venus. The probe flew by the planet on Dec. 14, 1962, and scanned the surface for 42 minutes.NASA/JPL  A technician wears a hood and protective goggles while working with a full-scale model of the Mariner spacecraft in a space simulator chamber at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., in 1962.NASA/JPL/Caltech

A technician wears a hood and protective goggles while working with a full-scale model of the Mariner spacecraft in a space simulator chamber at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., in 1962.NASA/JPL/Caltech  The Mariner 2 probe at an assembly facility in Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Aug. 29, 1962.NASA/JPL/Caltech

The Mariner 2 probe at an assembly facility in Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Aug. 29, 1962.NASA/JPL/Caltech